“Being up with the lark”, “the early bird catches the worm”, or “being a night owl” – these phrases are all familiar. A work-focused and digitally connected culture produces the notion of constant availability and the pressure of maximizing time, even if this comes at the expense of our sleep.

Looking at sleep patterns, there is a trend towards shorter sleep durations. With about one in four Europeans experiencing sleep problems [1], many people are suffering from acute and chronic fatigue, sleep disturbances or disorders such as insomnia. A German survey showed that 35% of adults often feel tired and have difficulties to concentrate during the day, and 20% frequently experience sleep disturbances [2]. Women are more often affected than men, and sleep disorders rise with increasing age [3].

Studies indicate that poor sleep is associated with significant direct and indirect costs for individuals and healthcare systems, with spill-over effects on labour markets and society. So, wouldn’t we actually benefit from rethinking towards a culture of healthy sleep habits? This article takes a closer look at the costs resulting from a “sleepless society”, taking the example of Germany.

Direct costs: healthcare resource utilisation

Insufficient sleep is linked with major short- and long-term health conditions, ranging from cancer and diabetes to anxiety and depression [4]. Especially in neurodegenerative disorder (NDD) and immune-mediated inflammatory disease (IMID) [5] patients are frequently affected. Poor sleep is not only a dominant symptom but can also contribute to the development and worsening of disease [6]. Consequently, sleep-deprived patients consume more healthcare resources and associated costs than patients without sleep problems [7].

In Germany, the total cost of disorders of initiating and maintaining sleep amounted to 922 million €. These costs arise from diagnostic tools (e.g., polygraphy, polysomnography), treatment (pharmacological, cognitive-behavioural therapy), prevention, rehabilitation and long-term care [8]. To give a more specific indication, more than 205,700 inpatient days linked to sleep disturbances were spent in German hospitals in 2018 [9].

Indirect costs: loss in productivity and quality of life

Sleep-deprived patients have a lower quality of life, are less able to perform activities of daily living and participate in social activities [10]. Furthermore, sleep disturbances can increase mortality and work absence while decreasing work and school performance. These factors add to the macro-economic loss of insufficient sleep, which was estimated to be around 1.56% of GDP in Germany in 2015, predicted to increase in the long-term [11].

The average sick leave due to poor sleep is comparatively low and accounts for a very small proportion of total work absence. However, data indicate that workers who are both ill and sleep-deprived take substantially longer and more frequent sick leave than workers who are ill but without sleep problems. This is especially the case for employees suffering from mental ill health, highlighting the significant impact of poor sleep on mental well-being [12].

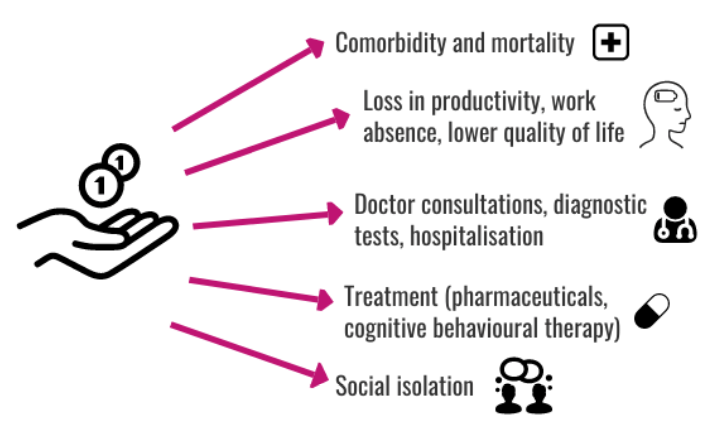

The figure below summarises the major direct and indirect cost indicators associated with sleep disturbances.

The exact burden is hard to measure

It can be assumed that the number of people affected by sleep disturbances is, in fact, much larger. The majority of those affected do not consult a doctor for their sleep problems, and, if they do, sleep disturbances are often not documented or diagnosed. Additionally, insufficient sleep is rarely noted by physicians as a reason for employees’ sick leave [3]. Therefore, it has to be kept in mind that quantifying the prevalence, direct and indirect costs of sleep disturbances is challenging.

A digital response to sleep disturbances and fatigue

Looking at these individual and societal costs, it becomes evident that an effective and efficient treatment of sleep disturbances and fatigue could result in substantial savings for patients, healthcare systems, insurance providers and labour markets. However, there is currently a lack of tools to comprehensively assess sleep problems and general fatigue. The IDEA-FAST project aims to tackle this gap through identifying and validating digital endpoints for reliable measurements of the severity and impact of fatigue and sleep disturbances among NDD and IMID patients. The remote monitoring could enable early personalised treatment, support care planning and enhance disease knowledge. Thereby, the above-mentioned costs could translate into benefits such as healthcare resource liberation, patients’ engagement, improved productivity and quality of life.

References

- Van de Straat, V., & Bracke, P. (2015). How well does Europe sleep? A cross-national study of sleep problems in European older adults. International Journal of Public Health, 60(6), 643-650. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00038-015-0682-y

- Deutschland schläft gesund e.V. (2018). Forsa-Umfrage Mai 2018 – Schlafstörungen. Deutsche Stiftung Schlaf. [online] Available at: https://deutschland-schlaeft-gesund.de/wp-content/uploads/2018/06/180620_DSG_Pressekonferenz_Handout.pdf

- BARMER. (2019). Gesundheitsreport 2019 – Schlafstörungen. [online] Available at: https://www.barmer.de/blob/200600/be5371374ee8e7463bb077cb6567b843/data/dl-gesundheitsreport2019.pdf

- Medic, G., Wille, M., & Hemels, M. E. (2017). Short- and long-term health consequences of sleep disruption. Nature and science of sleep, 9, 151–161. https://doi-org.ezproxy.ub.unimaas.nl/10.2147/NSS.S134864

- The diseases covered in the IDEA-FAST project: Parkinson’s Disease, Huntington’s Disease, Rheumatoid Arthritis, Systemic Lupus Erythematosus, Primary Sjögren’s Syndrome, Inflammatory Bowel Disease.

- Rozich, J. J., Holmer, A., & Singh, S. (2020). Effect of lifestyle factors on outcomes in patients with inflammatory bowel diseases. The American Journal of Gastroenterology, 115(6), 832–840. https://doi.org/10.14309/ajg.0000000000000608

- Strand, V., Shah, R., Atzinger, C., Zhou, J., Clewell, J., Ganguli, A., & Tundia, N. (2019). Economic burden of fatigue or morning stiffness among patients with rheumatoid arthritis: a retrospective analysis from real-world data. Current Medical Research and Opinion, 36(1): 161-168. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007995.2019.1658974

- Federal Office of Statistics. (2015). Krankheitskosten: Deutschland, Jahre, Krankheitsdiagnosen (ICD-10). [online] Available at: https://www-genesis.destatis.de/genesis//online?operation=table&code=23631-0001&bypass=true&levelindex=0&levelid=1611067803374#abreadcrumb

- Gesundheitsberichterstattung des Bundes. (2018). Diagnosedaten der Krankenhäuser nach Behandlungsort (ICD10-3-Steller, ab 2000). [online] Available at: https://www.gbe-bund.de/gbe/pkg_olap_tables.prc_set_hierlevel?p_uid=gastg&p_aid=776506&p_sprache=D&p_help=2&p_indnr=544&p_ansnr=54108266&p_version=2&p_dim=D.946&p_dw=14494&p_direction=drill

- Friedman, J. H., Brown, R. G., Comella, C., Garber, C. E., Krupp, L. B., Lou, J. S., … Taylor, C. B. (2007). Fatigue in Parkinsons disease: a review. Movement Disorders -New York-, 22(3), 297–308.

- Hafner, M., Stepanek, M., Taylor, J., Troxel, W. M., & van Stolk, C. (2016). Why sleep matters – the economic costs of insufficient sleep: A cross-country comparative analysis. Santa Monica, CA: RAND Corporation. [online] Available at: https://www.rand.org/pubs/research_reports/RR1791.html

- Marschall, J. et al. (2017). Gesundheitsreport 2017, Analyse der Schlafunfähigkeitsdaten. Update: Schlafstörungen. Beiträge zur Gesundheitsökonomie und Versorgungsforschung (Band 16). Hamburg: DAK-Gesundheit. [online] Available at: https://www.dak.de/dak/download/gesundheitsreport-2017-2108948.pdf